The story of the Chinese typewriter is one of cultural persistence against mechanical limitation. Western typewriters, with their small alphabet, could easily fit within a compact design. But in China, where literacy relies on thousands of unique characters, inventors faced a riddle: how to adapt a writing system deeply tied to culture, philosophy, and art into a machine made for speed and efficiency. The struggle itself reflects the balance between preserving heritage and embracing modernity.

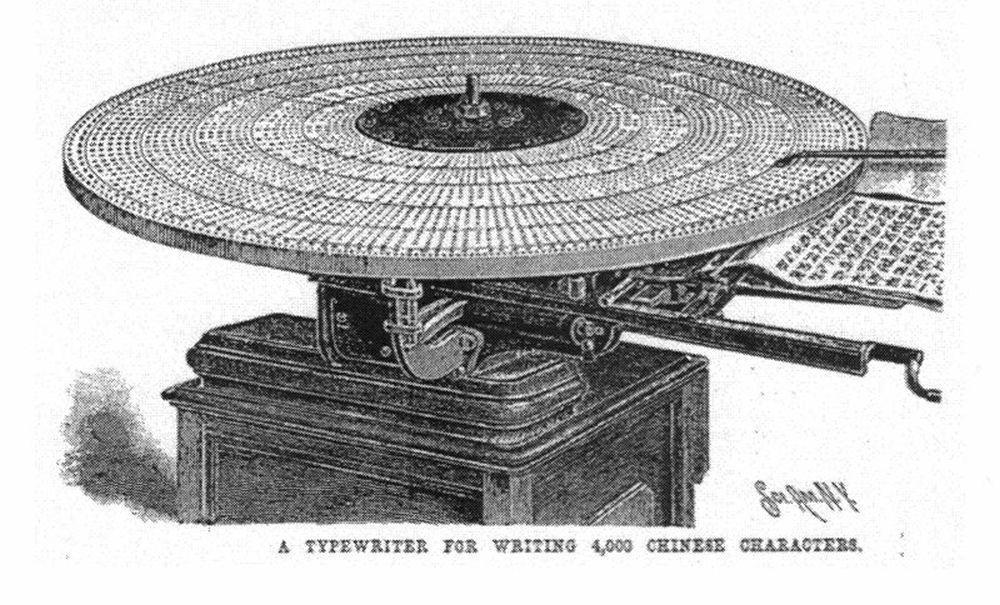

The earliest known attempt came from Devello Sheffield in the 1880s. His design used a rotating disk where characters could be selected one by one. It was clumsy, slow, and impractical, but it represented the first cultural translation of Chinese writing into Western industrial form. For a society that revered calligraphy as both an art and a moral discipline, this machine was less about replacing tradition and more about testing whether modernity could coexist with it.

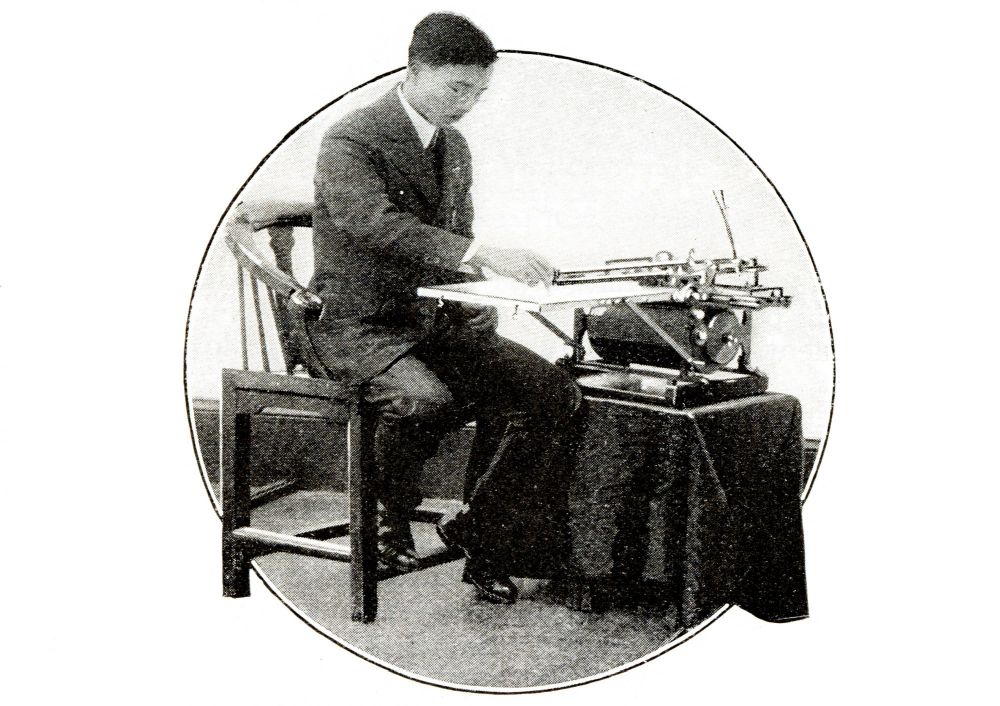

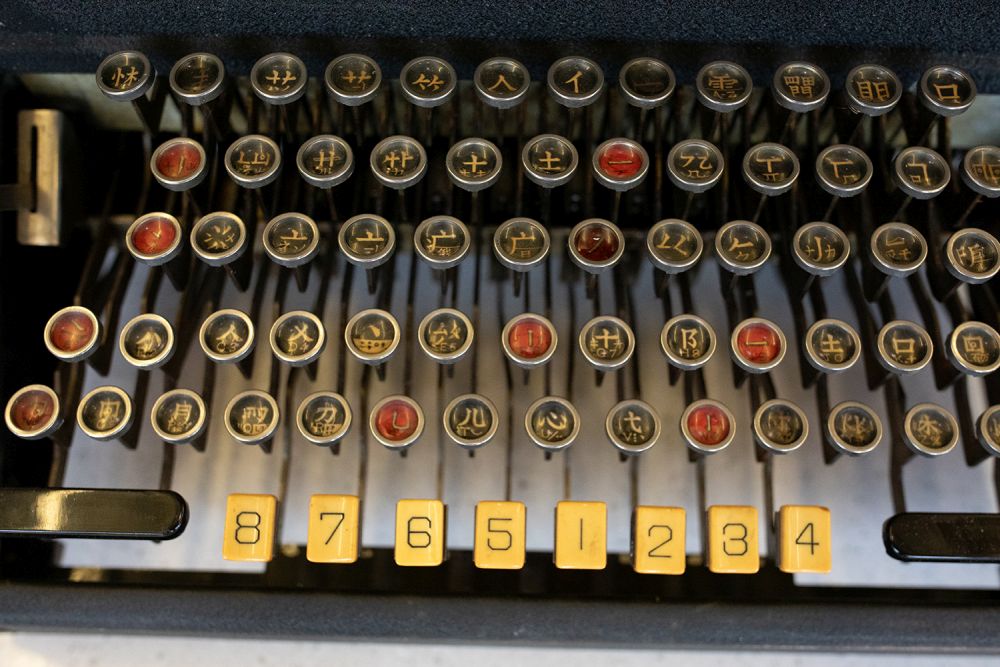

In the 1910s, Zhou Houkun created a cylinder-based typewriter, where thousands of characters were arranged and a sliding mechanism allowed operators to select the right one. It became one of the first truly usable Chinese typewriters. The cultural weight here is striking: Zhou’s invention allowed businesses, newspapers, and even government offices to produce documents more rapidly while still using the script that carried centuries of cultural meaning. Rather than abandoning characters for alphabetization, Zhou found a mechanical way to honor them.

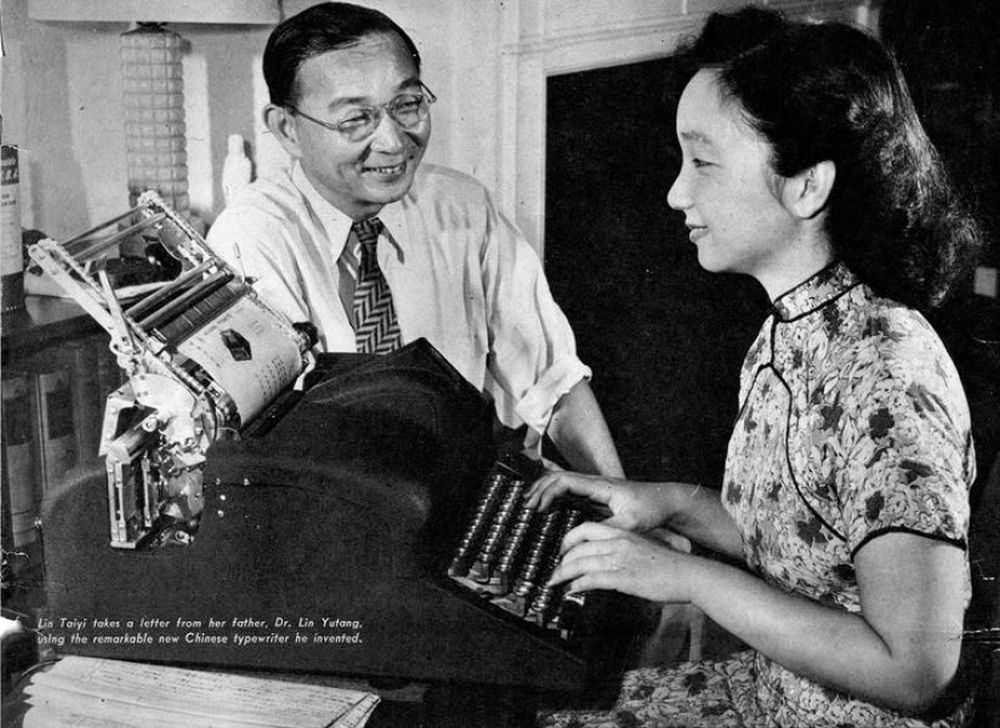

By the 1940s, the intellectual Lin Yutang designed the MingKwai typewriter. Lin’s aim was not just speed, but elegance. His “magic eye” index and component-based entry system embodied his vision of blending Chinese philosophy with modern technology. Though it failed commercially, culturally it symbolized the dream of reconciling the depth of Chinese tradition with the industrial promise of the 20th century. The MingKwai remains an icon of creativity and cultural pride in technological form.

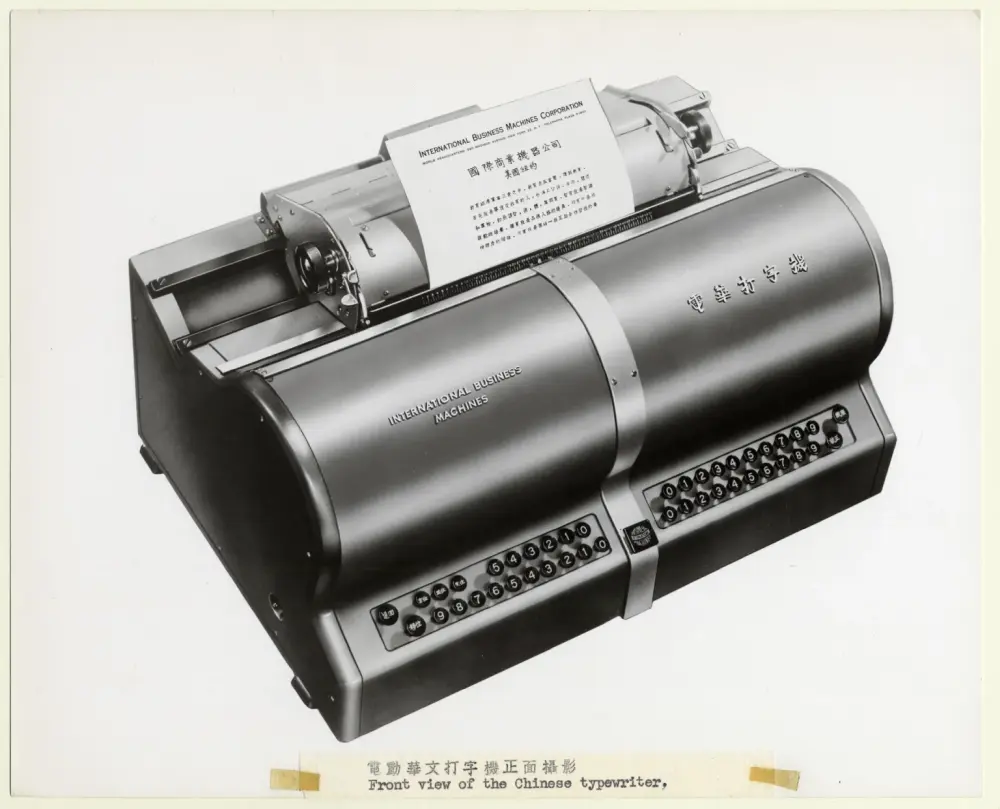

The Cold War years brought a new era, when IBM and engineer Chung-Chin Kao developed an electric Chinese typewriter that used encoding and efficient key systems. This wasn’t only about mechanics anymore—it was about bringing China’s writing into global communication networks. At a cultural level, this shift marked a turning point: Chinese script was no longer seen as a barrier to modernity but as a system worth integrating into the world’s most advanced technologies.

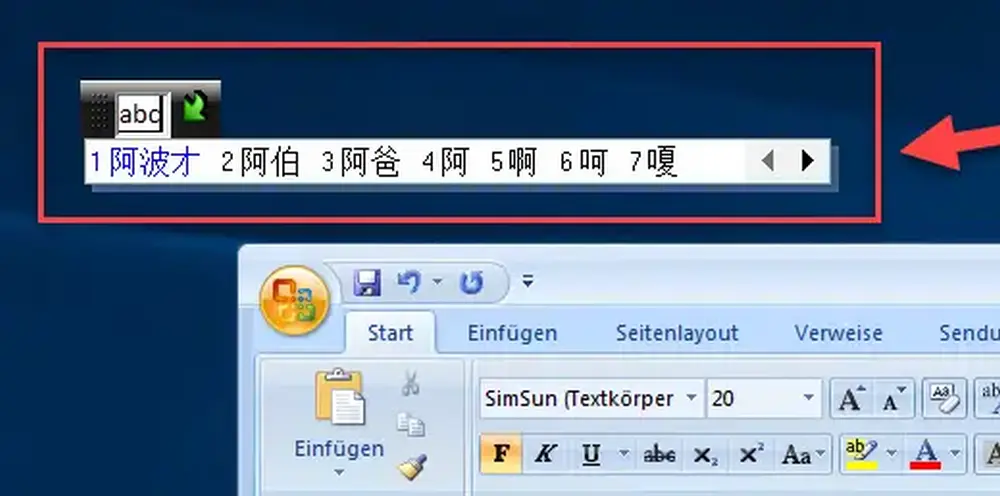

The arrival of computers transformed everything again. Input methods like Pinyin and shape-based IMEs resolved the mechanical challenges that haunted inventors for a century. Suddenly, the massive character set was no longer a burden. Instead, digital technology celebrated the richness of Chinese script, making it globally accessible while ensuring that the cultural heart of written Chinese—the characters themselves—remained untouched. What began as a struggle to squeeze tradition into a machine ended as proof that tradition could adapt and thrive in the digital age.

Images: Web and Wikipedis