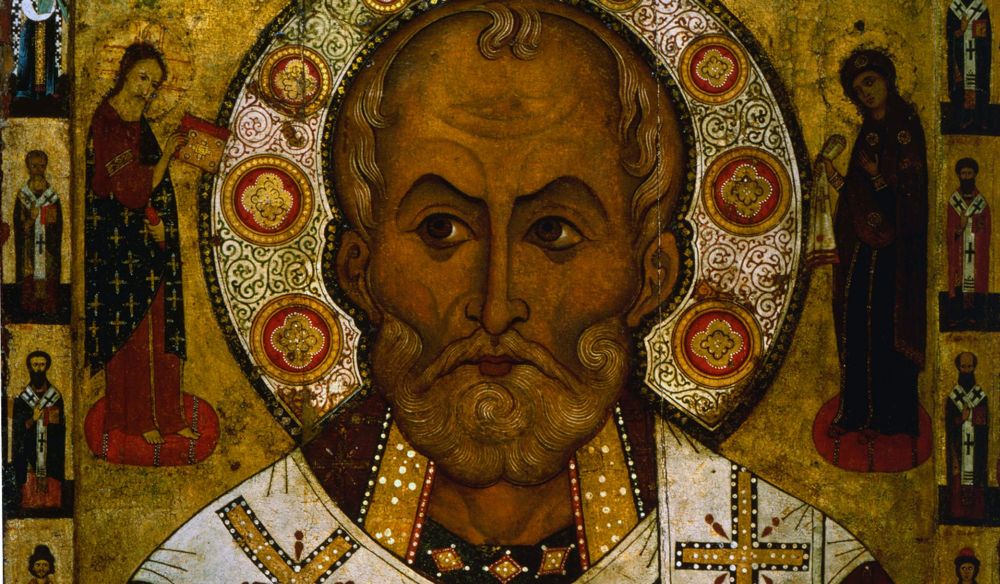

Saint Nicholas is one of those figures who quietly shaped the entire landscape of winter traditions, even if most people only know the modern echoes of his story. Long before the red suit, the reindeer, and the Coca-Cola glow, there was a 4th-century bishop in Myra, a coastal city of the Eastern Roman Empire. His reputation came not from sermons or authority but from a habit of slipping help to those who needed it when no one was watching. The stories that survived tell of coins left for families in trouble, food given with no name attached, and an unwavering attention to children and the poor. Kindness done secretly tends to stick in memory, and his name became associated with protection, generosity, and the idea that good deeds don’t need a witness.

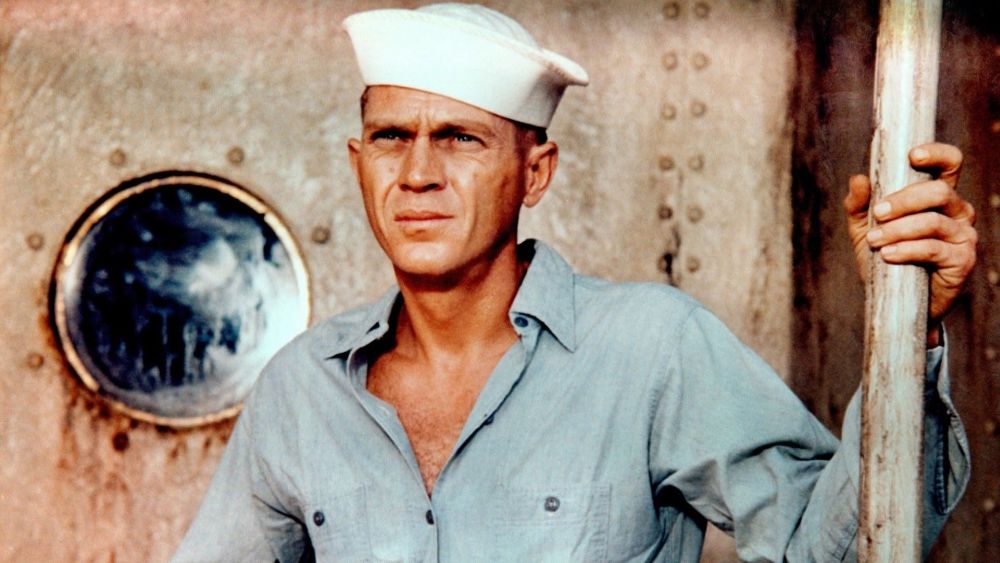

As centuries passed, Europe didn’t forget him. Instead, it multiplied him. Cities adopted him as their patron, sailors prayed to him for safe passage, and children waited for the early days of December to see what small surprises he might bring. In places like Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, France’s eastern regions, and across much of Central and Eastern Europe, December 6 became a bright spot in the cold. Children polished their shoes, placed them by doors or windows, and woke to find nuts, oranges, chocolates, or little gifts. Adults treated it as a reminder that generosity doesn’t require grand gestures. The celebration had a gentle intimacy: no fireworks, no pressure, just a moment shared within families and local communities.

But traditions travel, especially when people do. By the 17th century, Dutch settlers carried their beloved “Sinterklaas” across the Atlantic to the New World. His name slid into English as “Santa Claus,” and from there the transformation accelerated. American writers and illustrators began reshaping him. Washington Irving gave him a pipe and a sense of humor. Clement Clarke Moore’s poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” gave him reindeer, a sleigh, and a personality. The 19th century wrapped him in fur-lined clothes. The 20th century dipped him in bright red and commercial sparkle. What remained unchanged was the core: a figure who arrives quietly, bringing delight and reminding people that generosity has power.

It’s fair to say that without Saint Nicholas, modern Christmas wouldn’t look the way it does. He is the link between early Christian charity, medieval folklore, and the global end-of-year rituals that dominate December today. The idea that a mysterious giver comes at night, that small gifts appear for children, that kindness has a season — all of that traces back to him. Even the symbolism of stockings, shoes, and night-time visits grew directly from his legends.

Yet there’s something almost poetic about the way his story survived. It wasn’t preserved by institutions but by families, towns, and children repeating the same simple gestures across generations. A bishop who preferred anonymity became one of the most recognizable cultural figures on the planet, even if his original face is mostly forgotten. His celebration still lives on in Europe every December 6, more modest than Christmas, more rooted in local identity, and somehow more personal. And in the wider world, his spirit keeps resurfacing each time a child hangs a stocking or a gift appears with no name attached.

Saint Nicholas isn’t just a historical character. He’s a reminder that traditions grow from human impulses — generosity, imagination, and the desire to create a bit of magic for others. Everything else, from the North Pole to the glowing sleigh, is just evolution. The heart of it never changed.

Images : Web

Text : Scribblegeist (Ghost of the runaway pencil)