When the guns of the Opium War thundered in 1839, Taiwan was far from the epicenter of battle. The fighting raged in Canton, along the Yangtze, and on the coast of mainland China. Yet, even as the Qing Empire faced humiliation and defeat, Taiwan—then a relatively remote prefecture governed from Fujian—stood quietly on the sidelines. Its rugged mountains, dense forests, and indigenous communities kept it a frontier land, but its strategic location along the South China Sea meant it could not escape the shadow of what was unfolding across the strait.

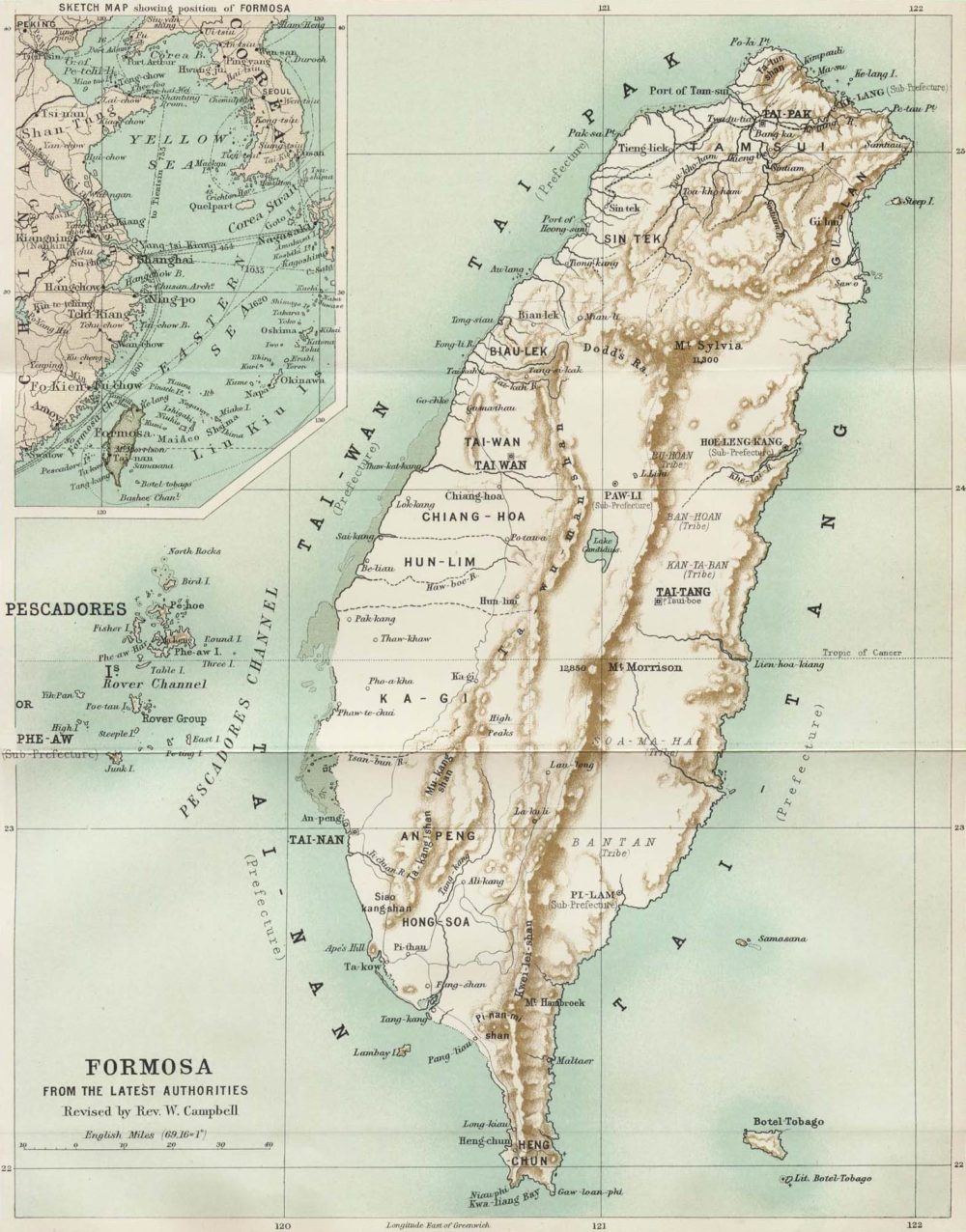

British commanders weighed Taiwan’s potential as a naval base while searching for a foothold in East Asia. They sent ships to survey Keelung and Tamsui, noting their coal deposits and anchorages. But the harbors were shallow and less defensible compared to Hong Kong’s deep natural port. In the Treaty of Nanking, it was Hong Kong that the British claimed, and Taiwan remained in Qing hands. Still, the surveys showed that the island was on the radar of Western powers, and in the decades to come, this attention would only grow.

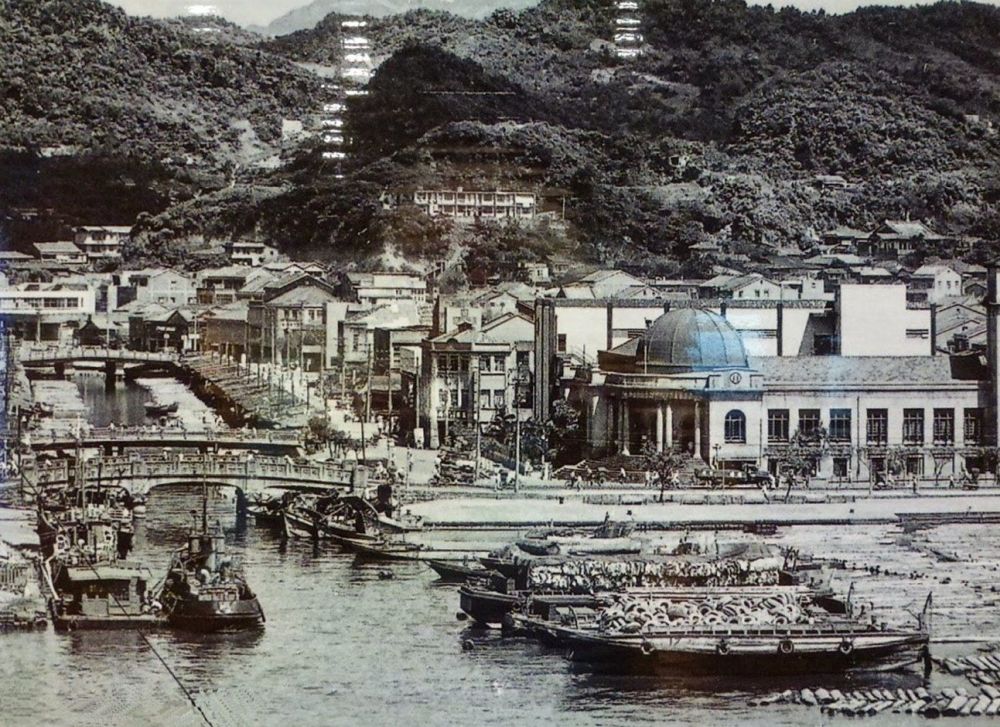

The First and Second Opium Wars pried open China’s doors to foreign trade, and Taiwan soon felt the ripple effects. Western merchants, especially British and American, began eyeing the island for its resources—camphor from the forests, coal from Keelung, tea from the hills. Missionaries followed, using the rights gained under the treaties with China to justify entry into Taiwan, often against the resistance of Qing officials. Ports like Tamsui and Anping became entry points for new global exchanges. Local communities found themselves drawn into encounters with foreign ships, traders, and religious missions that had been almost unheard of only a generation earlier.

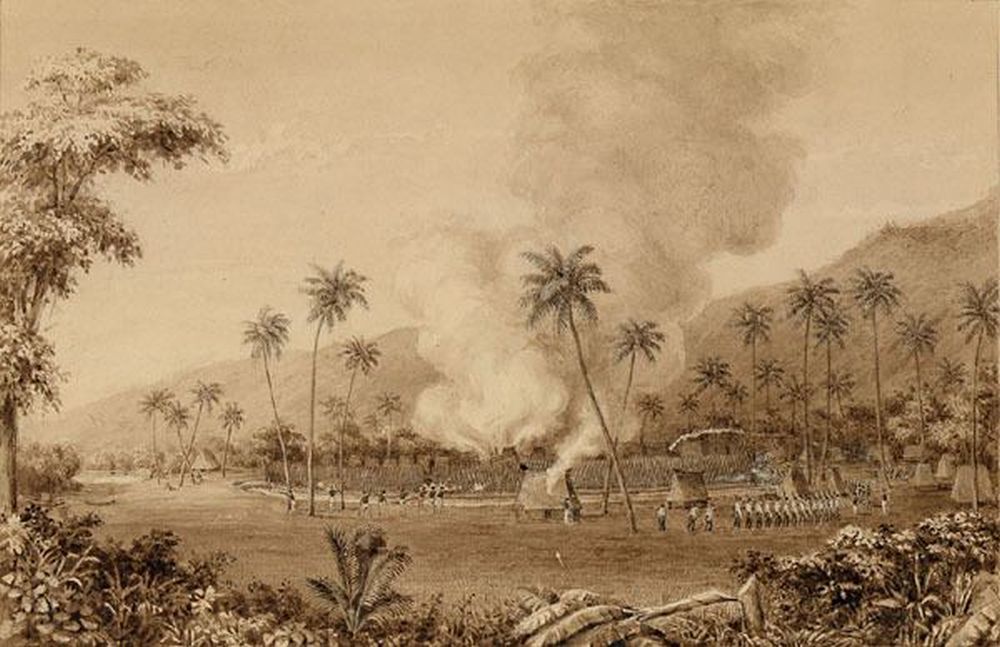

The new currents also brought friction. In 1867, the U.S. launched a punitive expedition in southern Taiwan after shipwrecked American sailors were killed by Paiwan warriors. The campaign ended in failure, but it underlined how Taiwan was no longer invisible to the world. A few years later, in 1884, the French blockaded Keelung and Tamsui during the Sino-French War, demonstrating again that the island had become a point of contest in imperial rivalries.

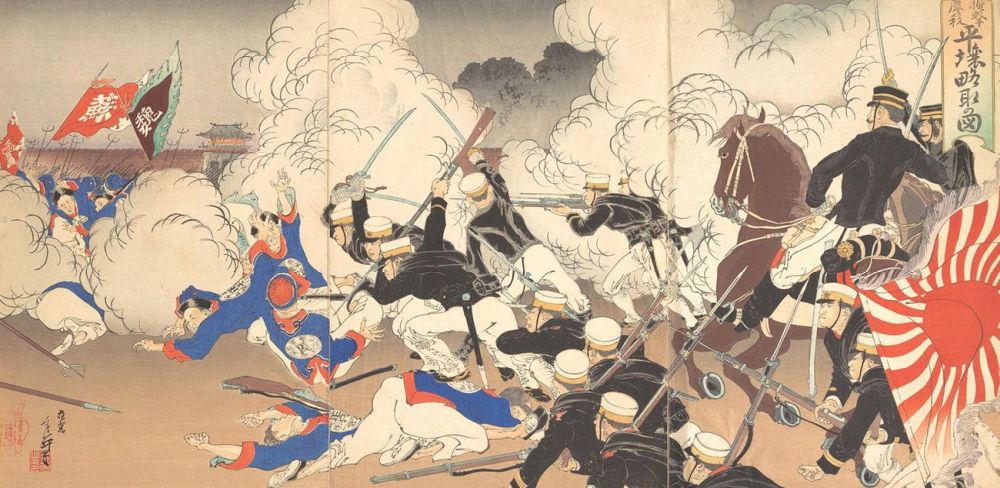

By the late nineteenth century, Taiwan’s place had changed from peripheral frontier to coveted prize. The very forces unleashed by the Opium Wars—the collapse of Qing control, the hunger of foreign powers for trade and strategic bases, the scramble for Asia—drew Taiwan deeper into the global picture. When Japan claimed the island in 1895 after the First Sino-Japanese War, it was the culmination of decades of foreign interest set in motion by that first clash between China and the West.

Taiwan never hosted a battle of the Opium Wars, nor was it named in the treaties that reshaped China. Yet the wars were the spark that put it in the sights of global powers. What had been an overlooked island at the edge of empire was slowly transformed into a stage where the great contests of the nineteenth century played out.

Images : Web

Text : Scribblegeist (Ghost of the runaway pencil)